Colorado River Basin from the lens of the U.S.-Mexico border

Water Allocations and Bilateral Transfers

A lot has been written about the Colorado River Basin. Why is this post different? We are bringing a series of posts from the lens of the U.S.-Mexico border, as typically the analysis is done looking only at the U.S. side or at the Mexican side as stand-alone countries. In this series, we will convey the basics about the functioning of the Colorado River considering its characteristics, challenges, and opportunities for the U.S.-Mexico border economy. This post is the first of many that will help you quickly grasp the complexities of the system for both nations. We hope you find it informative.

Colorado River: One of the transboundary basins between the U.S. and Mexico

First, it is important to understand that the Colorado River Basin is a transboundary (shared) basin between the countries of the U.S. and Mexico. The basin has a set of legal documents that regulate how water is allocated across both economies and distributed among the states in the U.S. This set of rules is commonly called the law of the river. If you want to dig deeper into the law of the river, there are several great resources available: Bureau of Reclamation, Central Arizona Project and Utah State Archives. In our posts on the Colorado Basin, we will give you a quick overview of how it all works.

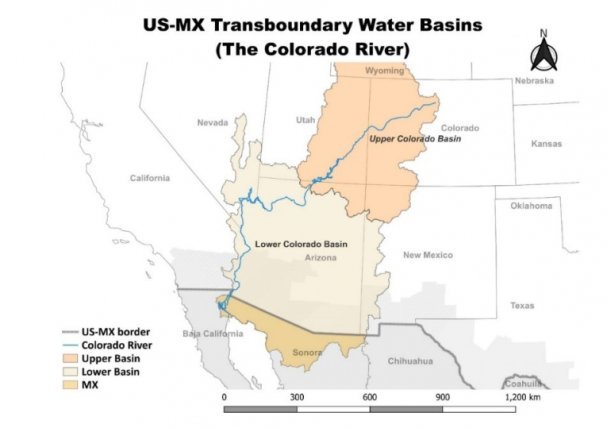

Below is how the Colorado River basin looks. It occupies an area roughly equivalent to the size of Texas. The river originates in the Rocky Mountains in Colorado and flows southwest to the Gulf of California (or Sea of Cortes/Mar de Cortes as it is known in Mexico). As the river only flows southward, the bilateral agreements in the law of the river only consider water transfers from the U.S. to Mexico. One important detail is that on the Mexican side, the river is mostly dry, but initiatives and conservation efforts to bring the river back are somewhat in place.

Source: NADBank staff

The basin is divided into two sections on the U.S. side. The Upper Colorado River Basin and the Lower Colorado River Basin.

- The Upper Basin comprises the states of Colorado (CO), New Mexico (NM), Utah (UT) and Wyoming (WY).

- The Lower Basin includes California (CA), Arizona (AZ), and Nevada (NV).

- The basin also includes water that must be delivered from the U.S. to Mexico, with all the water allocated to Baja California and Sonora on the Mexican side.

How is water allocated among the main subdivisions of the basin?

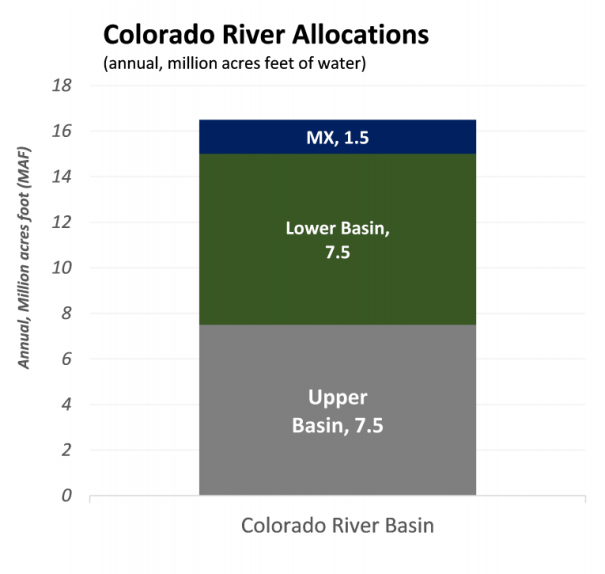

Water from the river is annually apportioned as follows:

- On the U.S. side, the Upper and Lower Colorado river basins have an annual allocation of 7.5 MAF (million acre-feet, equivalent to 9,251 hm3) for each section per the 1922 Colorado River Compact.[1]

- The U.S. must send an annual allocation of 1.5 MAF (1,850 hm3) a year to Mexico as established in 1944 Water Treaty.[2]

- Therefore, annual water allocations from the river total 16.5 MAF (20,352 hm3).

Source: NADBank staff based on 1922 compact and the 1944 treaty.

Note: The treaty also considers 0.2 MAF for Mexico in case of a surplus.

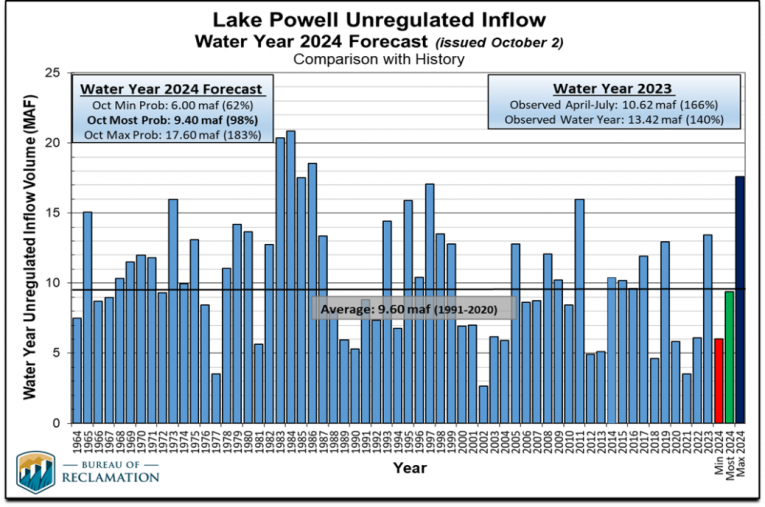

Inflows to the river from precipitation and snowmelt have varied significantly over the years and are key for water distribution to the states and Mexico. It is estimated that 92% of the natural flow of the river originates at the Upper basin. Therefore, water availability at Lake Powell, the last reservoir in the upper basin, is key to the entire system.

[1] The 1922 compact divides the basin into upper and lower basins and allocates 7.5 MAF to each part of the basin.

[2] The 1944 water treaty grants 1.5MAF to be delivered from the U.S. to Mexico and an additional 0.2MAF in case of a surplus.

On average (1991-2020) water inflows to Lake Powell are estimated at 9.6 MAF (11,841 hm3) a year, far below the basin needs of 16.5 MAF. However, unregulated inflows to Lake Powell tend to vary drastically from year to year.[3] For example, inflows for water year 2023 (from October 2022-september 2023) were 13.42 MAF (140% above average) but are expected to decline to 7.6 MAF (9,374 hm3) in water year 2024 (most probable scenario) as estimated in the 24-Month Study as of December 2023. The figure below shows how water has fluctuated over the years in this lake.

Source: Bureau of Reclamation.

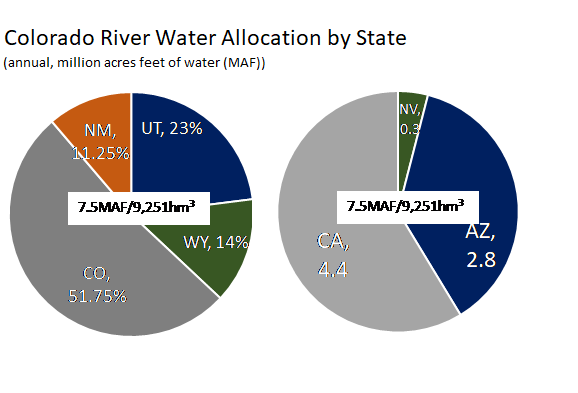

How is water allocated among the U.S. states?

Now, although water is allocated equally between the Lower and Upper Colorado basins, allocations for each U.S. state are not distributed the same way. In the Lower basin, California gets 4.4 MAF, followed by Arizona with 2.8 MAF and Nevada with 0.3 MAF. These allocations of the Lower basin were established in 1928 with the Boulder Canyon Project Act. It is important to note here that senior rights are at play. In the U.S., senior rights refer to the idea of “first in” and “first in right” or a doctrine of prior appropriation, in which the first users of the resource prevail over users that come later and play a key role in giving California greater or senior rights. Senior rights are also key to discussions about how much water allocations will be cut for each state and Mexico in times of drought. We will discuss these adjustments in the next post.

[3] Unregulated inflows refer to flows observed or estimated at stream gage, excluding upstream reservoirs. https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/g4000/riverops/model-info.html

Source: NADBank staff based on the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact of 1948 and the Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928. CO(Colorado), NM (New Mexico), UT(Utah), WY(Wyoming), CA(California), AZ(Arizona), NV(Nevada)

In the Upper basin, the allocation of water is not set at levels. Rather, water is allocated in the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact of 1948 as a percentage of the water available for the upper part. Let’s remember that the river starts in the Rocky Mountains and flows south. Consequently, the Upper basin needs to guarantee the delivery of 7.5 MAF of water at Lee’s Ferries, the point that divides the upper and lower basins. Since river flows change over time, the amount of water available for the Upper basin also changes. The 7.5 MAF in the upper basin is allocated among the states as shown in the chart above.

How about the states in Mexico?

In Mexico, of the 1.5 MAF (1,850 hm3) allocated by the U.S., 90.7% (1,677.54 hm3) goes to Baja California and 9.3% (172.69hm3) to Sonora on an annual basis.

Source: Cila/IBWC.

Source: Cila/IBWC.

Where does the U.S. deliver water to Mexico?

Water deliveries from the U.S. to Mexico are made at two points on the border. Water for Baja California is delivered at the northern international land boundary (known as Lindero Internacional Norte in Mexico) where Morelos Dam, a diversion dam, is located. Water for Sonora is sent through the Canal Sanchez Mejorada in San Luis Rio Colorado at the southern international land boundary (Lindero international Sur)

Source: NADBank staff.

Source: NADBank staff.

What’s next?

Current climate change conditions, with abnormal precipitation patterns, temperature changes and prolonged droughts have caused a rapid decline in water availability in the region, further complicating and worsening water gaps. To adjust to water conditions and protect the basin, predefined water shortages have already been established for the member countries and states. In the next post, we will discuss the current adjustments and the importance of Lake Mead—the largest reservoir in the basin and in the U.S.—in triggering cuts in water allocations for members.

*The views expressed in the article belong solely to the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinion or position of NADBank*

Post Categories: Water